For the first four national censuses (1801-1831) overseers of the poor or 'other substantial householders' collected information for their respective parish, township, tithing or quarter. Each completed a 'Form of Answers by the Overseers'. These answered a short series of questions which arrived at a series of raw statistics: the number of houses, families, individuals by sex and a limited range of occupational categories.

In Scotland, from 1801 until 1851, enumeration duties were principally carried out by the official schoolmaster in each parish - known as 'the Dominie'. Other recruits included doctors, clergymen, lawyers and merchants.

The first two censuses, namely 1801 and 1811, did not include the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man or Ireland. In 1821, an added - although discretionary - question asked for a breakdown of the population by sex and age group (under 5 years, 5-10, 10-15, 15-20, then by decade, and finally if over 100).

Some overseers decided to go above and beyond and compiled lists of names, of which nearly 800 survive for England.

1841 marked a revolutionary change in how the census was compiled, processed and utilized.

It was now nominal (name-based), rather than simply numeric.

The administration of the 1841 census took place at the recently founded General Register Office for England and Wales (GRO), with the first Registrar General, Thomas Henry Lister (1800-1842), serving as the first census commissioner.

The census registration districts were based on those employed for the civil registration of births, marriages and deaths. District Registrars divided their sub-districts into yet smaller enumeration districts, with each administered by temporary local enumerators.

In 1841 the 619 civil registration districts were divided into a total of 35,000 enumeration districts. In 1851 there were 30,441 enumerators in England and Wales (separately, custom house and coastguard officers enumerated merchant seaman and those on the waterways).

In 1871 the number of enumeration districts rose to 33,000.

Taking the Census (1851) by George Cruickshank.

Enumerator: 'What! not made out the list yet?!'

Head of family: 'Why no; it isn't such an easy matter as you may think for; However, let me see; there's John & Tom & Bill & Susan & Harry & Sarah & Dick & Eliza & Septimus...

District Registrars could appoint anyone of their choosing, providing they met the basic requirements:

'He must be a person of intelligence and activity; he must read and write well, and have some knowledge of arithmetic; he must not be infirm or of such weak health as may render him unable to undergo the requisite exertion; he should not be younger than 18 years of age or older than 65; he must be temperate, orderly and respectable, and be such a person as is likely to conduct himself with strict propriety, and to deserve the goodwill of the inhabitants of his district.'

Enumerators in England and Wales included relieving officers, constables and other peace officers. In the countryside farmers were called upon. As in Scotland, many schoolmasters were also employed.

Each enumerator was issued with the required number of household census forms (schedules), a pre-printed census enumerators' book (CEB) and a memorandum book; plus

an instruction book detailing their duties. In the week preceding Sunday census night, they handed each household a schedule with instructions. Should the head of the household be illiterate, a schooled family member or neighbour might help; otherwise the enumerator would assist at the time of collection the following day. If partially complete, the enumerator would request missing details on the doorstep.

In a letter to The Times (11 April 1861) an enumerator reported on his experience of conducting his second census in a poor neighbourhood: 'In most families...there was, if not a grown-up person, a boy or girl who had had sufficient schooling to enable them to fill up the schedule, and, failing this, it was taken to the baker's, or the publican's, or the chandler's shop, or to the rent collector...'

Sometimes personal bias would rear its head. For example, in London's Limehouse district in 1871 a census-taker recorded every prostitute under occupation as 'fallen'. In turn, some of their clients were wryly noted as 'Gentleman (Query)' and 'Jack of all trades (Nothing)'.

Once sorted, the enumerator then transcribed the completed schedules into their CEB; the census-taker's name can be found on the front page. Enumerators (in addition to Superintendent Registrars and District Registrars) could be landed with a fine of between 40 shillings and £5 for wilfully false declarations.

In 1841 they were permitted to use pre-defined abbreviations for certain occupations (For a list, see our table of Abbreviations to describe Occupations). Also in that year forenames were frequently abbreviated, for example 'Jas.' for James. To further save on time, ditto marks or 'Do' were frequently employed in surname, occupation and birthplace columns.

In 1841 entries were made in pencil, but come 1851 pen and ink were required. A single diagonal penstroke / marked the end of a household, whereas a double penstroke // marked the end of a building. This applied to the censuses from 1841 to 1901, save 1851 when a line was ruled halfway across the page for a household within a building and across the full page at the end of building.

Enumerators also completed summary tables in their CEBs, providing the number of houses and persons on each page.

Once complete, the books and schedules were dispatched - following (theoretical) checking by the District Registrar and Superintendent Registrar - to the Census Office in London. Census clerks then checked and analysed the data. Having used them as reference, the original schedules were destroyed.

This system ran from 1841 to 1901. The 1911 census marked the first time household schedules were kept, which negated the need for CEBs (special institutional schedules were still transcribed into enumeration books though).

In the case of Institutions (prisons, workhouses, asylums etc.) the master or keeper served as enumerator and completed a special schedule book, which they then forwarded to the Superintendent Registrar. For more information read our blog article Special Census Returns.

Enumerators were paid from 1841, but they were not salaried GRO employees. In the early censuses many considered the pay inequitable to the amount of work they put in.

In a letter to the editor of the Morning Advertiser (18 December 1841) entitled 'The Census', an enumerator wrote 'Sir, - Will you oblige a constant reader of your valuable journal by informing him whether there is any just cause for the delay in the payment by the district Registrar of our small pay for that troublesome undertaking, being unfortunately one of the unpaid enumerators for the St. Peter's district, Hammersmith, and what proceeding will be best for the recovery of the same. X.Y.Z,' This was over six months after that year's census!

In addition to letters, they voiced their gripes and concerns in their ECBs, in the knowledge that they would be seen 'up the line'. The enumerator for Mortlake in Surrey entered the following in his 1871 book: 'Very badly paid. I think if Government Officials had to do it, they would be paid treble the Amount.'

Poor enumeration inevitably discouraged universal diligence amongst recruits and dissuaded a proportion of higher-quality applicants. If paid out of their own pocket, enumerators could employ an assistant to deliver schedules and perform other set tasks.

Some enumerators had understandable concerns about approaching certain households in cramped and squalid urban areas. Their duties were not made any easier by a general distrust of authority and widespread illiteracy. They could easily be mistaken for the unwelcome 'rent man' in towns and cities.

On 13 June 1841, a week after that year's census, The Planet reported that 'In most of the parishes in and around the metropolis, very little difficulty was expereiced by the enumerators in obtaining the proper returns, with the exception of certain portions inhabited by the lower orders, in some of which it was deemed necessary that the enumerators should be accompanied by a policeman, an order to which effect was last week issued by the Commissioners of Police.'

The Times of 20 May 1871 reported on enumerators' post-census meetings. At one it was said that the work 'was not only difficult in many cases, but not altogether free from danger, an enumerator present having caught smallpox while discharging his duties.'

Complaints centred on the fact that a flat fee did not allow for the self-evident differences between districts. With time remuneration became fairer and better organized. In 1871 they received a sum of one guinea, plus two shillings and sixpence for every 100 persons above the first 400, sixpence for each mile when distributing schedules and the same amount per mile above five on collecting.

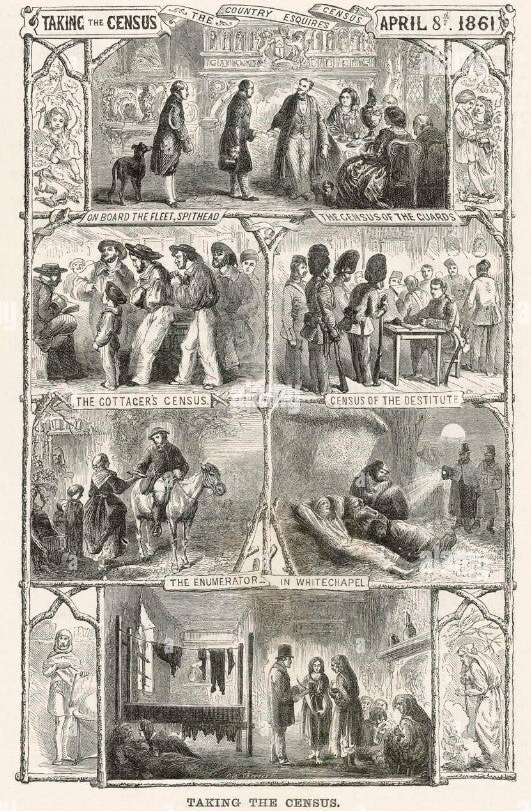

Taking the Census April 8th 1861.

From the top, the illustrations are variously entitled: 'The Country Esquire's Census; On Board the Fleet, Spithead; The Census of the Guards; The Cottager's Census; Census of the Destitute; The Enumerator in Whitechapel.

The need to assist the illiterate with schedule-filling was monitored in 1871. In parts of Manchester this reached 25%, whilst in Welsh-speaking Anglesey parishes the majority were completed by enumerators. Extremely wide variations were recorded in the six districts of Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire, from 5.3% to 64.7%.

On 4 April 1881, the day after the census, The Times wrote: 'The celerity [swiftness] and smoothness of the enumeration mark the perfection of modern administrative machinery.'

The mean age for enumerators was in the mid-forties, but in 1881 a 16-year-old farmer's son surveyed 1,924 people in a part of Worcester (as seen earlier the age stipulation was 18-65).

By 1891 the rapid growth of some districts meant some enumerators had notably more households to enumerate than others. For the first time female census-takers were recruited, though on forms a sole printed 'Mr' still appeared after the 'Name of the Enumerator'. A 1994 study identified at least 34 women employed in 1891.

In 1891 and 1901 enumerators in the East End of London (an area with a high Jewish population) gave out specially translated schedules in Yiddish and German. These aided speakers in the correct completion of the English version.

In 1901 enumerators had to brave snow, hail and high winds in their attempt to deliver schedules. The Western Daily Press (3 April 1901) reported on the sad tale of Charles Tanner, an enumerator in Winchester. Having collected all his schedules he went to the River Itchen 'took off his coat and overcoat, folded them up neatly, with his hat on top, and his bag containing his census papers by the side, and jumped into the river.'

The enumerators' lot was complicated in 1911 by the Suffragette boycott. Protestors disrupted census-taking in one of three ways: total evasion, providing minimal information or spoiling their schedules. For more information read our blog article 'No vote, No Census': the Suffragette Boycott of the 1911 Census.

The enumeration of bargees, June 1921.

Census night in 1921 was scheduled for 24 April, but a general strike (later cancelled) meant it was postponed until 19 June, making it the first summer census since 1841.

(1,854)

Create Your Own Website With Webador